100 Grams of Fat Per Day Diet

"Eat fat and get fat."

That's what mainstream diet "gurus" used to say not so long ago, back when low-fat diets reigned and low-fat foods crowded the shelves.

Much to obesity researchers' dismay, though, the war on fat didn't stop us from getting fatter and fatter.

And so the quest for a "better way" continued.

Well, fast forward to today and many people will tell you the hunt is over.

We finally understand the human metabolism well enough to say that the previous generation of scientists had it all wrong. Backward, actually.

"Eat fat and burn fat," we're now told.

This latest "revelation" has spread through the health and fitness space like chain lightning, giving rise to its own cottage industry of high-fat diets, cookbooks, and food products and supplements.

Unfortunately, though, this advice is just as flawed as its antithesis. In fact, and ironically, the exact opposite happens when you eat fat.

When you eat fat, you gain fat. But that doesn't mean it makes you fat.

I know that sounds cryptic, but don't worry–by the end of this article, it will all make sense.

You'll know exactly how much fat you should consume per day, what types of fat your body needs and why, what types of foods are best, and more.

So, let's start with a clear definition of terms and then move on to diet composition.

- What Is Dietary Fat?

- How Many Grams of Fat Should You Eat Per Day?

- The Bottom Line on How Many Grams of Fat Per Day

Table of Contents

Would you rather watch a video? Click the play button below!

Want to watch more stuff like this? Check out my YouTube channel!

What Is Dietary Fat?

There are two different types of fat found in food:

- Triglycerides

- Cholesterol

Triglycerides comprise the bulk of our daily fat intake and are found in a wide variety of foods ranging from dairy to nuts, seeds, meat, and more.

Fats can be in liquid (unsaturated) or solid (saturated) and they help maintain health in many ways: they help you absorb vitamins, they are used to create various hormones, they keep your skin and hair healthy, and much more.

Cholesterol is scarcer in our diets and is found in foods like eggs, liver, some fish, butter, and more.

It's a waxy substance present in all cells of the body, and it's used to make hormones, vitamin D, and substances that help you digest your food.

Several decades ago, it was believed that foods that contained cholesterol, like eggs and meat, increased the risk of heart disease. We now know it's not that simple.

Eggs, for instance, have been more or less exonerated, and research shows that processed meat is associated with high incidence of heart disease but red meat is not.

One of the reasons for these subtleties is foods that contain cholesterol also often contain saturated fat, which can increase the risk of heart disease (which we'll learn more about soon).

Another reason has to do with how cholesterol travels throughout your body.

It's delivered to cells by molecules known as lipoproteins, which are made out of fat and proteins. There are two kinds of lipoproteins:

- Low-density lipoproteins (LDL)

When people talk of "bad" cholesterol, they're referring to LDL.

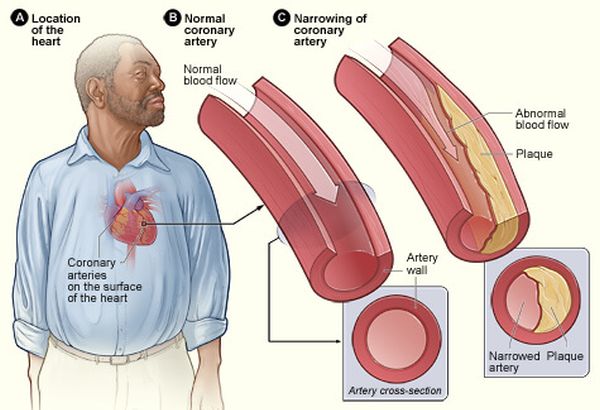

Research shows that high levels of LDL in your blood can lead to an accumulation in your arteries, which increases the risk of heart disease.

Here's what this looks like:

This is why research shows that foods that can raise LDL levels, such as fried and processed foods as well as foods with saturated fat, can increase the risk of heart disease.

- High-density lipoproteins (HDL)

HDL is often thought of as the "good" cholesterol because it carries cholesterol to your liver, where it is removed from the body.

So, now that you have the 50,000-foot view of dietary fat, let's zoom in on the type we eat the most of and thus are most concerned with: triglycerides.

Want a free custom meal planning tool?

Quickly calculate your calories, macros, and even micros for losing fat and building muscle.

Sending...

Your free stuff is on the way!

Looks like you're already subscribed!

What Is Saturated Fat?

Saturated fat is found in foods like meat, dairy products, eggs, coconut oil, bacon fat, and lard.

If a fat is solid at room temperature, it's a saturated fat.

The long-held belief that saturated fat increases the risk of heart disease has been challenged by recent research, which has been a boon to the fad diet industry, not to mention the meat and dairy industries (we've seen a veritable renaissance of meat and dairy consumption).

The problem, however, is that the research used to promote this movement has also been severely criticized by prominent nutrition and cardiology researchers for various flaws and omissions.

These scientists maintain that there is a strong association between high intake of saturated fatty acids and heart disease and that we should follow the generally accepted dietary guidelines for saturated fat intake (less than 10% of daily calories) until we know more.

Given the research currently available, I don't think we can safely say that we can eat all the saturated fats we want without any health consequences.

And I'd rather "play it safe" and wait for further research before joining in the saturated fat orgy.

What Is Unsaturated Fat?

Unsaturated fat is found in foods like olive oil, avocado, nuts, and fish. If a fat is liquid, it's unsaturated fat.

There are two distinct types of unsaturated fats:

- Monounsaturated fat

Monounsaturated fat is liquid at room temperature and starts to solidify when it's cooled.

Foods high in monounsaturated fat include nuts, olive and peanut oil, and avocado.

- Polyunsaturated fat

Polyunsaturated fat is liquid at room temperature and when cooled.

Foods high in polyunsaturated fat include safflower, sesame, and sunflower seeds, corn, and many nuts and their oils.

Unlike saturated fat, there's no controversy over monounsaturated fat.

There's evidence that it can reduce the risk of heart disease, and it's believed to be responsible for some of the health benefits associated with the Mediterranean diet, which involves eating a lot of olive oil.

Polyunsaturated fat, on the other hand, isn't as cut-and-dried.

The two primary polyunsaturated fats are alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) and linoleic acid (LA).

ALA is what's known as an omega-3 fatty acid and linoleic acid is an omega-6 fatty acid. These designations refer to the structure of the molecules.

ALA and LA are the only types of fat that we must obtain from our diets because they are essential to our health and our bodies can't produce them, which is why they're referred to as essential fatty acids.

That is, you could completely remove saturated and monounsaturated fat from your diet and survive, but if you were to eliminate ALA or LA, you would eventually die.

(Granted, this would be incredibly hard to do because even the worst of diets provides sufficient ALA and LA to prevent a true deficiency.)

Now, the controversy with polyunsaturated fat is centered on the ratio between ALA (omega-3) and LA (omega-6) intake.

The number of effects these two substances have in the body is enormous, and the chemistry is complex, but here's what you need to know for the purpose of this article:

- LA is converted into several compounds in the body, including the anti-inflammatory gamma-linolenic acid, as well as the pro-inflammatory arachidonic acid.

- ALA can be converted into an omega-3 fatty acid known as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), which can be converted into another calleddocosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

EPA and DHA are also found in high amounts in fatty fish. When you take a fish oil supplement, you're providing your body with EPA/DHA.

A massive amount of research has been done on EPA and DHA, and it appears that they bestow many, if not all, of the health benefits generally associated with ALA.

These benefits include…

- Reduced risk of heart disease

- Decreased inflammation

- Improved mood

- Faster muscle growth

- Increased cognitive performance

- Faster fat loss

- And much more…

It's an over-simplification to say that the effects of LA (omega-6) are generally "bad," and effects of ALA (omega-3) are generally "good," but it's more accurate than inaccurate.

And that's why it has been hypothesized that a diet too high in omega-6 and too low in omega-3 fatty acids can cause a whole host of health problems.

Newer research casts doubt on this, though.

There's no question that inadequate omega-3 intake is bad for your health, but ironically, studies have found that increasing omega-6 intake can decrease the risk of heart disease, not increase it.

Thus, scientists suspect that the absolute amount of omega-3 fatty acids in the diet is more important than the ratio between omega-6 and omega-3. This is why a considerable amount of work is being done to boost the omega-3 content of various foods like eggs and meat.

The bottom line is if your diet is even halfway sensible, you're getting enough omega-6 fatty acids. You may not be getting enough omega-3s (and EPA and DHA in particular), though.

This is less likely if your diet provides a fair amount of ALA, however, because it's converted into EPA, which can then be converted into DHA.

The problem with this, however, is the process whereby ALA is converted into EPA is quite inefficient (and conversion into DHA is even worse) and impacted by the amount of LA in your diet (a high-LA diet decreases conversion rates).

This is why relying on ALA as your sole source of omega-3 fatty acids may result in an EPA/DHA deficiency, and why it's smart to include fatty fish or a fish oil supplement in your diet.

What Is Trans Fat?

Trans fat is a type of unsaturated fat that occurs naturally in some meat and dairy foods, and is manufactured industrially by infusing vegetable oil with hydrogen.

The result is a "partially hydrogenated vegetable oil," which you'll find in many processed foods because it increases shelf life.

I'm not one for dietary absolutism, but there's little argument at this point that artificial trans fats should be eliminated entirely from our diets.

Studies show that relatively small amounts of these fats can increase the risk of a whole host of health problems, including heart disease, Alzheimer's, breast cancer, depression, and more.

To quote a review conducted by scientists from Harvard:

"TFA [trans-fatty acid] consumption causes metabolic dysfunction: it adversely affects circulating lipid levels, triggers systemic inflammation, induces endothelial dysfunction, and, according to some studies, increases visceral adiposity, body weight, and insulin resistance.

"…

"Consistent with these adverse physiological effects, consumption of even small amounts of TFAs (2% of total energy intake) is consistently associated with a markedly increased incidence of coronary heart disease."

(Interestingly, research also shows that naturally occurring trans fats aren't nearly as harmful to our health as artificial.)

How Many Grams of Fat Should You Eat Per Day?

Now that we understand what dietary fat is and its different forms and physiological functions, let's talk intake.

If you've done any other reading on the subject, you're probably expecting a pat recommendation like "20 to 30% of daily calories with less than 10% coming from saturated fat."

Well, the problem with a rule of thumb like that is it works fine for your average, sedentary person, but isn't optimal for us fitness folk.

Our bodies have absolute needs for essential fatty acids, not needs relative to caloric intake, which can be quite high due to body composition and activity level (especially when we're "bulking").

For example, I weigh about 190 pounds, and if I were the average, sedentary type, my body would burn about 2,000 calories per day.

Based on that, the "20 to 30% rule would provide 45 to 80 grams of fat per day, which is a reasonable range.

I exercise 6 days per week and have quite a bit of muscle, though, so my body burns about 3,000 calories per day.

Based on that, my recommended fat intake skyrockets to 65 to 115 grams per day, but does my body really need that much more fat because it's muscular and I exercise regularly?

No, it doesn't.

Eating that much fat wouldn't be harmful to my health, of course, but it would limit the amount of carbohydrate I could eat. And generally speaking, the lower your carb intake is, the harder it's going to be to build muscle and strength.

This is why I'm generally an advocate for eating enough fat to support overall health while maximizing carbohydrate intake, which precludes high-fat dieting (you only get so many calories per day, unfortunately).

The bottom line is if your body does well on a high- protein, high-carb diet, and low-/moderate-fat diet, it's going to serve you best in your quest to build a great physique.

So, with that out of the way, let's look at how much fat you should be eating.

How Many Grams of Fat Per Day to Lose Weight?

If you're to listen to some people, dietary fat is the key to losing body fat.

Eat large amounts of "healthy fat," they say, and little carbohydrate, and you'll lose weight.

Hogwash.

Energy balance and protein intake govern the rate at which you lose fat, which is why research shows low-carb, high-fat dieting offers no weight loss benefits.

In fact, a recent study conducted by scientists at the National Institutes of Health found that calorie for calorie, low-fat dieting is more effective for fat loss than low-carb.

Furthermore, studies show that bodybuilders following a high-protein, high-carb, low-fat diet lose less muscle than those following a high-protein, low-carb, high-fat diet.

This isn't particularly surprising given the fact that carbs help preserve resistance training performance and decrease muscle breakdown rates, mainly through replenishing glycogen stores and elevating insulin levels.

All this is why I recommend a high-protein, high-carb "weight loss diet" that provides adequate fat for general health needs.

And how much fat is needed for general health, you ask?

Well, research shows that around 0.3 grams per pound of fat-free mass per day is adequate for maintaining health.

(And "fat-free mass" is everything in your body that isn't fat, i.e., muscle, water, and bone.)

This comprises 15 to 20% of daily calories for most people. (And if you're not sure how to work out how many calories you should eat every day, read this article.)

What types of fat you eat is also important.

As you know, you want to limit your saturated fat intake, avoid artificial trans fats, and favor monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, paying particular attention to your omega-3 intake.

This dietary approach to weight loss is ideal for both health and body composition.

Specifically, I recommend you get the majority of your dietary fat from monounsaturated fats, that you keep your saturated fat intake at or below 10% of daily calories, and that you attention to your EPA/DHA intake.

Regarding your EPA/DHA intake, 500 mg per day (combined) would be a bare minimum, but I recommend something closer to 2 grams per day because it confers a variety of health and performance benefits.

The easiest way to get there is to eat several servings per week of fatty fish like Alaskan salmon, Arctic char, or Atlantic mackerel, or take a fish oil supplement every day.

I really don't like the taste of fatty fish, so I opt for supplementation. Here's what I use:

How Many Grams of Fat Per Day to Gain Muscle?

Many people claim that a high-fat diet helps you build muscle faster by increasing testosterone levels.

This is only partially true.

Yes, a high-fat diet can increase testosterone levels, but no, it's not going to help you build muscle faster.

There are several reasons for this.

A high-fat diet can increase testosterone levels…but not by enough to help you get bigger.

One study showed that men getting 41% of daily calories from fat had 13% more free testosterone than men getting just 18% of daily calories from fat. Another study conducted a decade earlier showed similar results.

That might sound good on paper, but research clearly shows it's not nearly enough to move the muscle-building needle.

For example, a study conducted by researchers at McMaster University investigated if the acute hormonal changes that happen during weightlifting affect muscle and strength gains.

The subjects were young, resistance trained men, and they did 5 weightlifting workouts per week and followed a standard "bodybuilding" diet.

After 12 weeks, scientists found that exercise-induced spikes in anabolic hormones like testosterone, growth hormone, and IGF-1 had no effect on overall muscle growth or strength gains.

That is, the size of the hormonal responses seen in the subjects varied widely but there was no significant difference in terms of muscle and strength gains.

Another study worth reviewing was conducted by researchers at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science.

This involved manipulating the testosterone levels of 61 young, healthy men using a combination of testosterone and drugs to inhibit natural testosterone production.

After 20 weeks, scientists found there was a dose-dependent relationship between testosterone and leg strength and power (higher testosterone levels meant more strength and power)…

…but the effects weren't significant until testosterone levels exceeded the top of the natural range by about 20 to 30% (about 1,200 ng/dL).

Now, this study does have an obvious limitation: the subjects weren't exercising.

The strength and power gains would have been higher if subjects had been weightlifting, of course, but it's telling nonetheless.

And just to lend further perspective on the matter, let's review a bit of steroid research.

Scientists at Maastricht University published an extensive review of studies related to the use of anabolic steroids in 2004 and found the following:

- Muscle gains in people lifting weights on steroids ranged between 4.5 and 11 pounds over the short term (less than 10 weeks).

- The largest amount of muscle gain over the short term was 15.5 pounds over the course of 6 weeks.

(In case you're wondering why the large variation in gains, a multitude of factors ultimately determined the results including training history, genetics, workout programming, diet, etc.)

Now, compare this to what you can achieve naturally and my point becomes clear:

Even when you blast your testosterone through the roof with drugs and add additional anabolic steroids on top, it doesn't necessarily mean you're going to gain "shocking" amounts of muscle.

And if that's the case with the sky-high testosterone levels that come with drug use, what does that tell us about small fluctuations that can occur within the physiological normal ranges?

It's just not going to make much of a difference except in the most extreme cases of, let's say, going from the absolute bottom of normal to the top.

So, similar to my recommendations for weight loss, I recommend that you eat a high-protein, high-carb, and moderate-fat diet when you're trying to build muscle.

This allows you to fully take advantage of the significant muscle-building benefits of both protein and carbs, as opposed to chasing negligible changes in hormones.

In terms of an actual amount, 0.3 grams of fat per pound of bodyweight is my general recommendation.

Everything we discussed earlier on limiting saturated fats, favoring unsaturated fats, and ensuring your EPA/DHA intake is adequate applies.

The Bottom Line on How Many Grams of Fat Per Day

Years ago, we were told to keep our dietary fat intake as low as possible.

While that may help control caloric intake, it's not optimal for health.

Since then, the pendulum has swung hard in the other direction and now millions of people are eating more dietary fat than ever before, including saturated fat, by eating large amounts of foods like…

- Meat

- Dairy

- Coconut or coconut oil

- Avocado

- Olive oil

- Nuts and seeds

This too may be increasing the risk of disease and, unfortunately, without even providing any significant health or performance benefits.

I believe the most sensible advice is this:

We should eat at least enough dietary fat to support our health, and only raise it based on our goals, fitness, and preferences.

For example, most physically active people wanting to build muscle or lose fat are going to do best on a high-protein, high-carb, low-/moderate-fat diet.

There are exceptions, of course, but that is true far more often than not.

Sedentary people needing to lose weight, however, will probably do better with a high-protein, low-carb, high-fat diet (carbohydrate is primarily energetic, so if you don't burn much energy, you don't need much of it).

The key is tailoring your diet to your needs, and I hope this article helps you do that.

What's your take on how many grams of fat you should be eating per day? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

+ Scientific References

- Hartgens F, Kuipers H. Effects of androgenic-anabolic steroids in athletes. Sport Med. 2004;34(8):513-554. doi:10.2165/00007256-200434080-00003

- Storer TW, Magliano L, Woodhouse L, et al. Testosterone dose-dependently increases maximal voluntary strength and leg power, but does not affect fatigability or specific tension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(4):1478-1485. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021231

- West DWD, Phillips SM. Associations of exercise-induced hormone profiles and gains in strength and hypertrophy in a large cohort after weight training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(7):2693-2702. doi:10.1007/s00421-011-2246-z

- Hämäläinen E, Adlercreutz H, Puska P, Pietinen P. Diet and serum sex hormones in healthy men. J Steroid Biochem. 1984;20(1):459-464. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(84)90254-1

- Dorgan JF, Judd JT, Longcope C, et al. Effects of dietary fat and fiber on plasma and urine androgens and estrogens in men: A controlled feeding study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64(6):850-855. doi:10.1093/ajcn/64.6.850

- Schwab U, Lauritzen L, Tholstrup T, et al. Effect of the amount and type of dietary fat on cardiometabolic risk factors and risk of developing type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer: A systematic review. Food Nutr Res. 2014;58. doi:10.3402/fnr.v58.25145

- Helms ER, Aragon AA, Fitschen PJ. Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: Nutrition and supplementation. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2014;11(1). doi:10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- Walberg JL, Leidy MK, Sturgill DJ, Hinkle DE, Ritchey SJ, Sebolt DR. Macronutrient content of a hypoenergy diet affects nitrogen retention and muscle function in weight lifters. Int J Sports Med. 1988;9(4):261-266. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1025018

- Garthe I, Raastad T, Refsnes PE, Koivisto A, Sundgot-Borgen J. Effect of two different weight-loss rates on body composition and strength and power-related performance in elite athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2011;21(2):97-104. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.21.2.97

- Hall KD, Bemis T, Brychta R, et al. Calorie for calorie, dietary fat restriction results in more body fat loss than carbohydrate restriction in people with obesity. Cell Metab. 2015;22(3):427-436. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.021

- Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. - PubMed - NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19246357. Accessed December 19, 2019.

- Lacroix É, Charest A, Cyr A, et al. Randomized controlled study of the effect of a butter naturally enriched in trans fatty acids on blood lipids in healthy women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(2):318-325. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.023408

- Micha R, Mozaffarian D. Trans fatty acids: Effects on metabolic syndrome, heart disease and diabetes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(6):335-344. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2009.79

- Sánchez-Villegas A, Verberne L, De Irala J, et al. Dietary Fat Intake and the Risk of Depression: The SUN Project. Brennan L, ed. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16268. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016268

- Chajès V, Thiébaut ACM, Rotival M, et al. Association between serum trans-monounsaturated fatty acids and breast cancer risk in the E3N-EPIC study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(11):1312-1320. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn069

- Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, et al. Dietary fats and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(2):194-200. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.2.194

- Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JAE, et al. Dietary fat intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1491-1499. doi:10.1056/NEJM199711203372102

- Rosell MS, Lloyd-Wright Z, Appleby PN, Sanders TAB, Allen NE, Key TJ. Long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in plasma in British meat-eating, vegetarian, and vegan men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(2):327-334. doi:10.1093/ajcn/82.2.327

- Goyens PLL, Spilker ME, Zock PL, Katan MB, Mensink RP. Conversion of α-linolenic acid in humans is influenced by the absolute amounts of α-linolenic acid and linoleic acid in the diet and not by their ratio. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(1):44-53. doi:10.1093/ajcn/84.1.44

- Gerster H. Can adults adequately convert α-linolenic acid (18:3n-3) to eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (22:6n-3)? Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1998;68(3):159-173. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9637947. Accessed December 19, 2019.

- Burdge G. α-Linolenic acid metabolism in men and women: Nutritional and biological implications. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7(2):137-144. doi:10.1097/00075197-200403000-00006

- Willett WC. The role of dietary n-6 fatty acids in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. In: Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine. Vol 8. ; 2007. doi:10.2459/01.JCM.0000289275.72556.13

- Johnson GH, Fritsche K. Effect of Dietary Linoleic Acid on Markers of Inflammation in Healthy Persons: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(7). doi:10.1016/j.jand.2012.03.029

- Couet C, Delarue J, Ritz P, Antoine JM, Lamisse F. Effect of dietary fish oil on body fat mass and basal fat oxidation in healthy adults. Int J Obes. 1997;21(8):637-643. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0800451

- Muldoon MF, Ryan CM, Sheu L, Yao JK, Conklin SM, Manuck SB. Serum Phospholipid Docosahexaenonic Acid Is Associated with Cognitive Functioning during Middle Adulthood. J Nutr. 2010;140(4):848-853. doi:10.3945/jn.109.119578

- Smith GI, Atherton P, Reeds DN, et al. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids augment the muscle protein anabolic response to hyperinsulinaemia-hyperaminoacidaemia in healthy young and middle-aged men and women. Clin Sci. 2011;121(6):267-278. doi:10.1042/CS20100597

- Sublette ME, Ellis SP, Geant AL, Mann JJ. Meta-analysis of the effects of Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1577-1584. doi:10.4088/JCP.10m06634

- Bloomer RJ, Larson DE, Fisher-Wellman KH, Galpin AJ, Schilling BK. Effect of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid on resting and exercise-induced inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers: A randomized, placebo controlled, cross-over study. Lipids Health Dis. 2009;8. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-8-36

- Simopoulos AP. The importance of the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. Exp Biol Med. 2008;233(6):674-688. doi:10.3181/0711-MR-311

- Plourde M, Cunnane SC. Extremely limited synthesis of long chain polyunsaturates in adults: Implications for their dietary essentiality and use as supplements. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007;32(4):619-634. doi:10.1139/H07-034

- Sofi F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Accruing evidence on benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on health: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(5):1189-1196. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2010.29673

- Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Monounsaturated fatty acids, olive oil and health status: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13(1). doi:10.1186/1476-511X-13-154

- Kromhout D, Geleijnse JM, Menotti A, Jacobs DR. The confusion about dietary fatty acids recommendations for CHD prevention. Br J Nutr. 2011;106(5):627-632. doi:10.1017/S0007114511002236

- Pedersen JI, James PT, Brouwer IA, et al. The importance of reducing SFA to limit CHD. Br J Nutr. 2011;106(7):961-963. doi:10.1017/S000711451100506X

- Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM. Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(3):535-546. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27725

- Kromhout D, Geleijnse JM, Menotti A, Jacobs DR. The confusion about dietary fatty acids recommendations for CHD prevention. Br J Nutr. 2011;106(5):627-632. doi:10.1017/S0007114511002236

- Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2010;121(21):2271-2283. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.924977

- Zazpe I, Beunza JJ, Bes-Rastrollo M, et al. Egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease in the SUN Project. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(6):676-682. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2011.30

Readers' Ratings

5/5 (22)

Your Rating?

Source: https://legionathletics.com/how-many-grams-of-fat-per-day/